Reducing Tier-II Operator Fitness Test Failure Rates for

Air National Guard Tactical Air Control Party

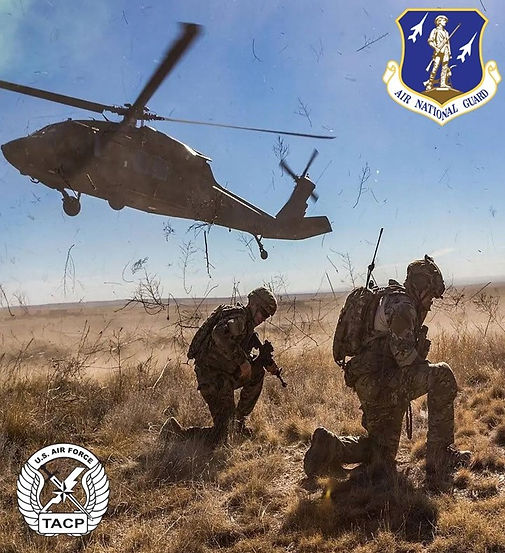

Air National Guard (ANG) Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) is an Air Force Weapon System within the Air Force Special Warfare Directorate of the United States Air Force (USAF). Their primary mission is to command and control strike assets against surface targets to meet the overall commander’s intent for an operation. The Airmen within this specialty are often the sole USAF representative to joint and coalition service partners. Their primary job is physically demanding and requires the Airmen to be in a consistent state of readiness to face the enemies of the United States worldwide, at a moment’s notice.

That high state of mission readiness comes with increased standards for their physical fitness assessments each year. ANG TACP must complete a Tier-II Operator Fitness Test (OFT) instead of the standard USAF Fitness Assessment each year. The Tier-II OFT comprises nine graded areas across several fitness domains deemed critical for specific mission areas by the USAF's Human Performance Optimization professionals and leadership. The standard USAF Fitness Assessment currently has three graded areas covering only muscular and cardiovascular endurance (Robson S. et al., 2021).

The Challenge

This needs assessment aimed to research performance gap areas, probable causes for those gaps, and provide possible intervention solutions to the client for implementation.

Our Process

The needs assessment team conducted a systematic needs assessment using evidence-based practices for determining gap areas, probable causes and selecting appropriate interventions to resolve performance gap issues within an organization and individual performers. The process utilized components from multiple frameworks and models, which were applied to a six-phase needs assessment: (1) Problem Identification; (2) Organization Analysis; (3) Environmental Analysis; (4) Gap Analysis; (5) Cause Analysis; and (6) Intervention Options. (Stefaniak, 2020).

Needs Assessment Goals

-

Conduct systematic needs assessment for our client

-

Provide evidence-based data and recommendations to our client for future action on the subject

-

Ensure systemic and systematic performance problems are addressed

Our Methodologies and Models

A

The needs assessment team used the performance analysis portion of the Harless model to assist in clearly defining the problem. The Harless Model’s smart questions (illustrated in the next section) provided our team with a series of questions for the client and for upstream stakeholders that assisted in clearly defining the current state and desired future state.

B

Rummler & Brache’s (R&B) 9-Box Model assisted with analyzing and organizing extant data, semi-structured interview responses, and possible survey inputs. R&B’s systems focus on the three interconnected performance levels and helped our team thoroughly investigate the client’s problem, focusing on the organization, process, and performer levels (Rummler-Brache Group, 2022).

C

Chevalier’s Updated BEM focused our attention on the distinction between environmental and individual factors that impact performance (Chevalier, 2003). Our team used the BEM as an additional, second-layer analysis of identified gaps in this needs assessment. Using the BEM as a second-layer analysis provided a structure to identify causes for performance gaps through the six factors; information, resources, incentives, motives, capacity, and knowledge/skills (Chevalier, 2003).

D

To identify interventions, the team began by linking performance gaps from Rummler and Brache’s 9-boxes with the causal areas (environmental- information, resources, and individual knowledge/skills) from Chevalier’s Updated BEM. From there, the team utilized Hale’s intervention types to align possible intervention types with those root causes (Hale, 2006). Once the team identified the types of interventions, we then referenced our data collection to provide specific examples that could apply to each intervention type, so the client received actionable data. When we matched Hale’s intervention types with specific interventions, we consulted with the client on a multi-criteria analysis for the types of interventions to provide a prioritized list of interventions.

Problem Identification

Using a portion of Harless' Front-End Analysis (FEA), the team set out to answer five "smart questions" to understand the client's problem. To answer the five questions, the team conducted an extant data review of various policy documents and articles related to mission readiness and semi-structured interviews with two upstream stakeholders.

Key Questions from Harless' FEA

- Do we have a problem, and what evidence proves that?

- Do we have a performance problem?

- How will we know when the problem is solved?

- What is the performance problem?

- Should we allocate resources to solve it?

Findings

The Tier-II operator fitness test pass rates within the ANG TACP are 70%. The client’s desired performance is increased pass rates to ≥95%. This 25% gap creates a 10% loss in combat capability for TACP Airmen across the USAF TACP community.

What's the Impact?

The client is concerned with the Air National Guard’s passing rate and potential impact on overall readiness for the USAF TACP formation. Specifically, the client believes that their Airmen will sustain higher injury rates in addition to higher failure rates for the Tier-II operator fitness test due to the lack of training and resources within the ANG.

Military readiness cannot be understated as a primary concern within this problem set. Military readiness is described as the capacity to engage in combat and fulfill assigned missions and tasks (Institute for Defense and Business, 2022). This aspect of the United States security strategy ensures that our department of defense personnel are sufficiently prepared to respond to orders or attacks at any time, anywhere around the globe. Since military readiness is greatly affected by the defense budget outlined by Congress, military personnel and leaders must constantly seek innovative ways to keep training and equipment maintenance as up-to-date as possible for their individual equipment and people (Institute for Defense and Business, 2022)

Organization, Environment, and Gap Analysis

Our data collection plan initially involved 1) an extant data review of policy documents provided by the client, 2) semi-structured interviews with direct impactees, upstream stakeholders, mid-stream stakeholders, and subject matter experts, and 3) survey results. Our team was unable to conduct surveys based on our project timeline and our access to a survey pool large enough to collect substantial data. We still recommend a survey tailored to the findings of this needs assessment (mainly the recommendations) to assess if the stakeholders value one recommendation over the other.

Our team conducted phases 2-4 simultaneously using Rummler and Brache's 9-box model as our systematic process. Overlaying all our data against Rummler and Brache’s 9-box model, we can see the performance gap areas of concern shown in the figure below.

When our team looked at common themes between the gaps, we could see that the process management was directly affecting the entire performance row. While the organization itself did not show any clear performance gaps we fully understood that the management of the process was directly correlating to the gaps we were seeing at the performer level. Improper process management, for example, directly results in the performer not having clear mechanisms for feedback and also doesn’t allow them to have a standard coaching program. That same process management gap does not allow the performer to have adequate tools or training which also directly affects their individual goals. The design of the process affects how the process is managed and the management affects how the process is designed so those two deficiencies cause a loop of gaps that need to be addressed.

When looking forward to our cause analysis and using the data from this gap analysis, our team identified that Chevalier's Updated BEM would allow us to focus our attention on the distinction between environmental and individual factors that impact performance (Chevalier, 2003). We would bring these five gap areas forward into our cause analysis to assist in identifying root causes and eventually apply intervention types to those causal areas.

Data Collection Methodology

Cause Analysis

Our team coalesced all of our data gathered and performed some additional literature reviews to establish clear diffusions of effects in performance gaps to assist in identifying causes. Utilizing Chevalier's updated Behavior Engineering Model (BEM), we could distinguish three clear causal areas shown below.

After identifying the causal areas, we revisited some of our data to draw specific correlations to identify and establish a root cause of the gaps, which would assist with prioritizing interventions with our client. We concluded that our main issue could be narrowed down to the environment-resources.

If we had to pick a single root cause for the performance gap, the resources area directly contributes to a lack of both environment-information and individual-knowledge/skills. While the environment-information can be a contributing factor as well, the literature reviews and interviews with subject matter experts all agreed that resourcing should be the first step in addressing passing rates and overall mission readiness of the force. In addition, we did not see a clear delineation pointing to individual knowledge as a root cause. Instead, that casual area appears to be directly influenced by both the environment-information and the environment-resources.

Intervention Options

The team utilized Hale’s Intervention Types to align possible interventions with our causal areas (Hale, 2006). Once the team identified the types of interventions, we then referenced our data collection to provide specific examples that could apply to each intervention type, so the client received actionable data. When we matched Hale’s intervention types with specific interventions, we consulted with the client on a multi-criteria analysis for the types of interventions to provide a prioritized list of interventions.

Intervention Types

Our team selected five intervention types from Hale's guide. These five types covered the primary causal areas that created performance gaps (Hale, 2006).

Multi-Criteria Analysis

We met with our client to discuss some of the criteria they were concerned with when implementing interventions. We used this data to score each intervention type and develop a path forward for the client based on their needs and concerns.

We presented our clients with a path forward based on their priorities. This plan gives our clients an executable program to move forward. We also noted that our data pointed to development being the key to success for their whole project but realized the financial barriers they face with that specific intervention type.

References

Bartley, J. (2021, August 30). Navigating Front-End Analysis. From Learning Solutions: https://learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/navigating-front-end-analysis

Chevalier, R. (2003). Updating the behavior engineering model. Performance Improvement, 8-14.

Code of Ethics. (2022, October 10). From International Society for Performance Improvement: https://ispi.org/page/CodeofEthics

Cody R. Butler, P., Lauren e. haydu, P., Jacob F. Bryant, B., John D. Mata, M., Juste Tchandja, P., Kathleen K. Hogan, M., & Ben

R. Hando, D. (2022, August). Musculoskeletal injuries during U.S. Air Force special warfare training assessment and selection, fiscal years 2019-2021. Medical Surveillance Monthly Report, 29(8).

Dale W. Russell, P., Joshua Kazman, M., & Cristel Antonia Russell, P. (2019). Body Composition and Physical Fitness Tests Among US Army Soldiers: A Comparison of the Active and Reserve Components. Public Health Reports, 134(5), pp. 502-513.

Elliot, V. (2018). Thinking about the coding process in qualitative data analysis. From https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol23/iss11/14/

Force, U. S. (2018, July 5). The Enlisted Force Structure. AFI 36-2618. Washington D.C.: United States Air Force.

Guthrie, L. C. (2022, October 27). Human Performance Branch Chief, Air Force Special Warfare. (M. J. Robertson, Interviewer)

HAF/A3S. (2021, March 15). TACP Strategic Communications Card. Washington D.C., USA: USAF.

Hale, J. (2006). The performance consultants field book: Tools and techniques for improving organizations and people (2nd Ed. ed.). Pfeiffer.

Institute for Defense and Business. (2022, November 6). What is Military Readiness. From Institute for Defense adn Business: https://www.idb.org/what-is-military-readiness/#:~:text=Military%20readiness%20serves%20a%20key,on%20the%20focus%20of%20preparation.

Lytell, M. C., Robson, S., Schulker, D., McCouland, T. C., Matthews, M., Mariana, L. T., & Robbert, A. A. (2018). Training Success for U.S. Air Force Special Operations and Combat Support Specialties: An analysis of Recruiting, Screening and Development Processes. Santa Monica: RAND.

Mansell, L. (2022, October 13). ANG TACP Functional Area Manager. (J. Roberston, Interviewer)

RummlerBrache Group. (2022, October 20). Process Improvement Certification Training. From RummlerBrache Group: https://www.rummlerbrache.com/

Rummler-Brache Group. (2022, November 6). Three Levels Of Performance. From RummlerBrache Group: https://www.rummlerbrache.com/sites/default/files/Overview%20Three%20levels%20of%20Performance.pdf

Scott, W. C., Hando, B. R., Butler, C. R., Mata, J. D., Bryant, J. F., & Angadi, S. S. (2022, November 16). Force plate vertical jump scans are not a valid proxy for physical fitness in US special warfare trainees. Frontiers in Physiology.

Stefaniak, J. E. (2020). Needs Assessment for Learning and Performance: Theory, Process, and Practice. New York: Routledge.

USERRA Overview. (2022, November 22). From U.S. Office of Special Counsel: https://osc.gov/Services/Pages/USERRA.aspx

Warha D, W. T. (2009). Illness and injury risk and healthcare utilization, United States Air Force battlefield airmen and security forces, 2000-2005. Military Medicine, 174(9), pp. 892-898.

William J. Rothwell, C. K. (2011). Human Performance Improvement (Second ed.). London and New York: Taylor & Francis Group.